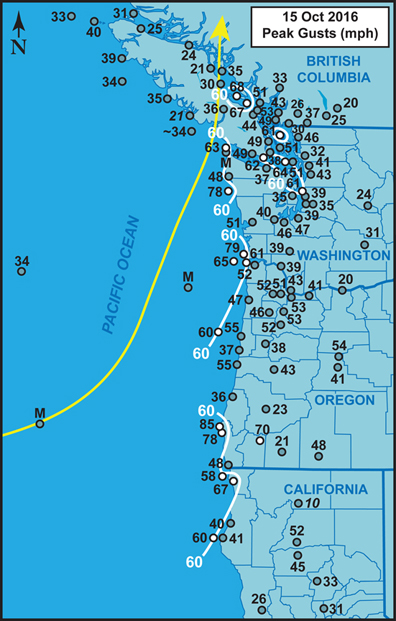

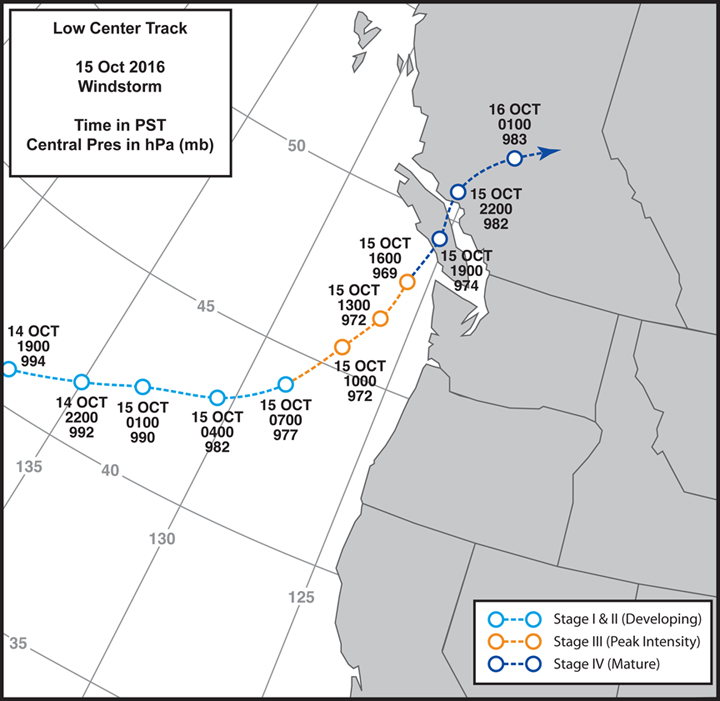

Figure 1.1 above Peak gusts (mph and km/h) for the October 15, 2016 windstorm. Wind speeds are largely from long-term surface airways weather observation sites, data buoys, lighthouses and C-MAN stations, with limited data from other networks (e.g. RAWS). Stations with long histories are preferred because of the research focus on inter comparison of historic storms. Numbers preceded by a tilde (~) represent the highest gust report in a dataset that has been interrupted at the height of the storm--usually data loss is from power outages. Values in italics are gusts estimated from peak wind, usually 2-minute or 5-minute, using a 1.3 gust factor. Stations with high-wind criteria gusts (≥58 mph or 93 km/h) are denoted with white-filled circles. Isotachs depicting ≥60 mph (~100 km/h) gusts are included to highlight the regions that had concentrations of the indicated magnitudes. The track of the extratropical cyclone center is shown (yellow arrow). Click on the map to see a larger version. Here is a map listing the station names. |

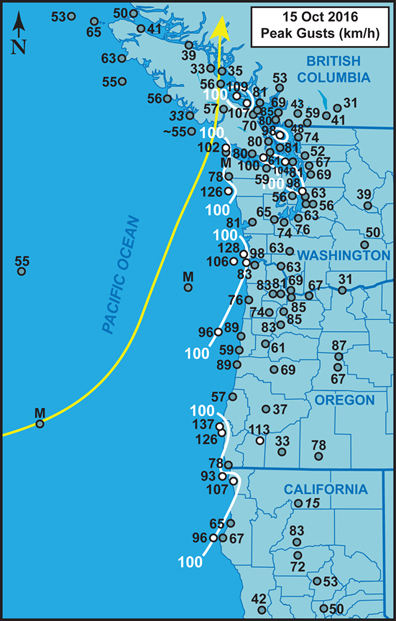

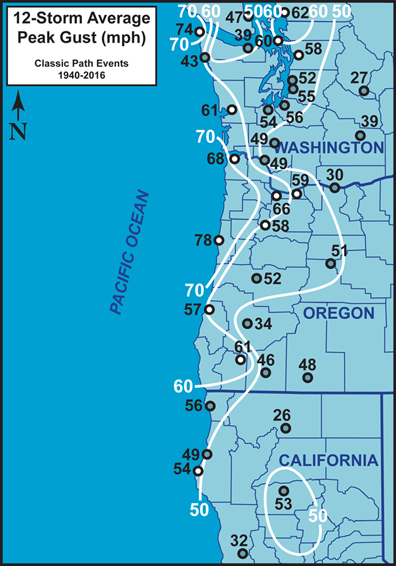

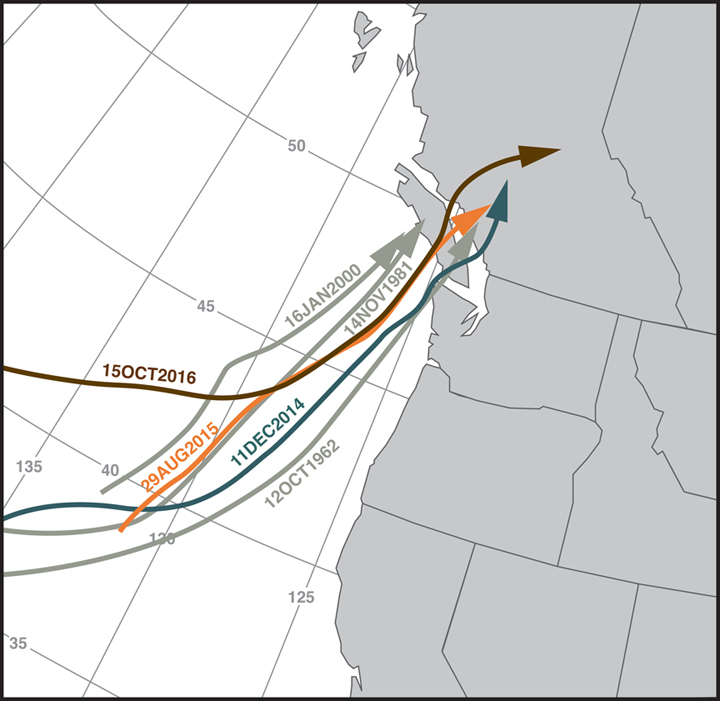

The Ides of October Storm grew from the remnants of Typhoon Songda, a western Pacific tropical cyclone. This is not an unprecedented situation, as there appears to be a link between many major Cascadia storms and tropical systems. The entrainment of deep tropical moisture provides a good energy source for a developing midlatitude cyclone. A link to a tropical storm is not a necessary ingredient for a major windstorm, but simply boosts the likelihood of such an event. One of the most familiar events with a tropical connection is the 1962 Columbus Day Storm and its association with Typhoon Freda. The October 21, 1934 windstorm also appears to have tropical roots. In most cases of typhoon entrainment, the tropical cyclone has strongly degraded before its remnants have been entrained in the midlatitude westerly flow. The Ides Storm resulted from a very rare case where the associated typhoon became entrained in the westerly flow while still fully intact. This may have had some bearing on the forecasting difficulty and the storm outcome. Looking at peak gusts for the Ides Storm, despite many variables in favor of high winds, including having a classic path, the early-season windstorm largely underperformed (Figure 1.1). There are many classic path windstorms in history that have produced a stronger outcome, especially in the most populated areas in the study region. On the coast, most of the stations that reported high winds were those that were well exposed, such as Cape Blanco and/or Destruction Island. Exposed in this context generally means has a large overwater fetch relative to the prevailing direction of the wind at the time of maximum gust. Stations that were even slightly sheltered, such as North Bend or Astoria, generally received far lower peak gusts than exposed sites even nearby. During all windstorms the exposed locations tend to report higher wind speeds--there is nothing unusual about this pattern. What is interesting here is that there is such a clear demarcation between exposed and sheltered sites, with high winds being restricted solely to the former. Also, the difference in peak wind speed between the exposed and sheltered sites appears to be a bit higher than usual, at least in some cases. At the exposed sites, peak wind gusts were generally 60 to 80 mph (100 to 130 km/h), and for the somewhat sheltered sites 35 to 55 mph (55 to 90 km/h). The story along the coast is the same for the interior, with high winds by and large being restricted to site with long overwater fetch. The southwest Oregon valleys were largely missed by this storm. This is in contrast to many classic windstorms that have delivered strong winds, including high wind gusts in some instances, to places like Medford. In the Willamette Valley, wind gusts generally ranged from 40 to 55 mph (65 to 90 km/h), strong, but nothing like the recent December 11, 2014 classic windstorm, which was run-of-the-mill for the classic path category. The relatively low wind response also occurred in the Puget Lowlands and North Interior of Washington and the Lower Mainland and Greater Victoria regions of British Columbia, with peak gusts generally between 35 to 50 mph (55 to 80 km/h). From a climatological perspective, the Ides storm produced a below average gust response. Using data form approximately 38 stations from northwest California to southwest British Columbia, the storm had an average peak gust of 41.6 mph (67 km/h). This is just 81% of a 12-storm average (1940-2016) for high-wind-generating extratropical cyclones following the classic path. In comparison, the December 11, 2014 windstorm produced a 47.8 mph (77 km/h) average, about normal, the November 13-14, 1981 windstorm 59.3 mph (95 km/h) and the 1962 Columbus Day Storm a phenomenal 75.6 mph (122 km/h). |