December 27, 2002 Minor Windstorm compiled by Wolf Read |

|

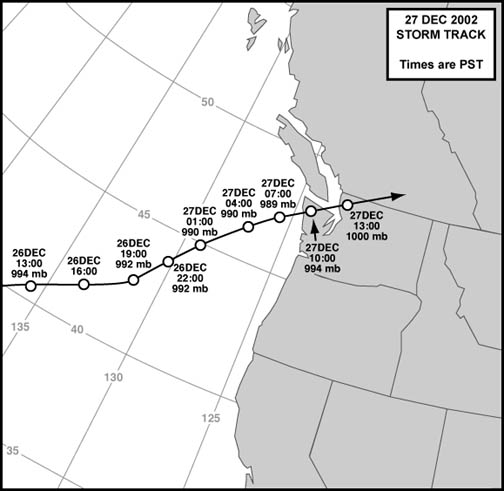

A fairly strong cyclone developed far off of Northern California on December 25 to 26, 2002, and then raced generally northeastward toward Washington's Olympic Peninsula. The track is detailed in Figure 1, above. With a minimum pressure of about 989 mb (29.21"), the low's center made landfall between 09:00 and 10:00 PST on December 27. Winds escalated south of the low's track as the storm swept inland, with south to southwest gusts reaching 50 to 65 mph at many locations on the coast, and 40 to 55 mph at many places in the interior. According to National Weather Service storm spotter reports, damage to structures and trees occurred in coastal communities, with scattered power outages. From personal contacts in the region, power was also lost at isolated locations in the greater Seattle area, including Bellevue. I saw some trees and large branches down in the Portland Metro area, with brief brownouts occurring at my home during the gale. A wooden fence was smashed by a large limb on E. Burnside near 39th. According to the Oregonian, an Olympia boy was electrocuted to death from a fallen powerline [1]. Outages were reported in Gresham, Cedar Hill and Banks. Two Gresham women were injured when a large branch broke from a tree and landed on them. Highways in the Coast Range, such as heavily-travelled 26, were blocked by fallen trees. The Seattle Times reported that the storm cancelled power to about 260,000 customers in the greater Puget Sound Area [2]. Most outages were in East King County. Two people were injured--one by a pickup canopy that took to the air in the gale. A wind gust threw a tractor-trailer rig onto its side on the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, forcing closure of the important commuter link. The Lake Washington floating bridges remained open. Here's what I noted about this storm in my journal: |

|

December 27, 2002: Meteorological Details The surface map for 10:00 HRS PST is shown in Figure 2, below. These are the conditions at approximately the time of my peak gust of 45 mph (09:44), and when winds just began reaching gale force in the greater Seattle area. Note the closely-packed isobars reaching from central Oregon to northern Washington. The isobars are oriented almost west-east over the region, a nearly ideal situation for strong ageostrophic (jumping the gradient) winds in the south-to-north trending valleys, such as the Willamette and the Puget Lowlands. The pressure gradient was strong, but a number of storms on record have exceeded this storm's highest values (more on gradients below). |

|

The 8-km resolution infrared satellite picture, Figure 3, below, shows the cloud conditions at the same time as the surface map above. The dry slot had become somwhat ill-defined by this time, which the storm's center in the gray area over the Olympic Peninsula. This cyclone didn't have a strongly developed bent-back occlusion, as evidenced by the warmer (darker) cloud tops north of the storm's center, when compared to say, the February 7, 2002 South Valley Windstorm and the December 16, 2002 storm. The bent-back was of moderate strength at best, though Bellingham did report brief heavy rain out of this feature from 11:08 to 11:10, then moderate rain up to 12:00, which totalled 0.15" from 11:53 to 12:00. Wind gusts out of 290 reached 18 mph at 11:53 HRS. Source: Satellite photo is courtesy of the University of Washington Archives for weather data. Bellingham's rain data is from the National Weather Service, Seattle office, METAR reports. |

|

The peak gusts for this windstorm are shown in the map below, Figure 4. This cyclone lashed the immediate coastline of Oregon and Southwest Washington with 55 to 75 mph gusts, the Willamette Valley and Southwest Washington Interior with 30 to 45 mph gusts, the Eastern Puget Sound region with 45 to 60 mph gusts and Washington's North Interior, San Juans and Strait of Juan De Fuca with 20 to 35 mph gusts. The cyclone's track, which carried the center south of Bellingham, spared Washington's northern regions the strong winds seen in the Puget Sound. For interior sections, the Sound was in the ideal location for high winds with this storm, being south of the center, and very close, where gradients were at their steepest. Source: Peak gusts are primarily from the National Weather Service, Eureka, Portland and Seattle offices, METAR reports, plus some from spotter reports, and National Data Buoy Center, realtime meteorological data. |

|

Examination of Some Interior Stations Wind and pressure conditions are plotted for Sea-Tac and Portland in Figures 5 and 6, below. Conditions were quite similar between the two observation sites, indluding wind duration and direction. The differences are in lower pressures at Sea-Tac, with faster winds. And Seattle's barometer climbed at a faster rate as the low pulled away. These differences were probably due to Sea-Tac's closer proximity to the cyclone's center. Source: Hourly data are from the National Weather Service, Portland and Seattle offices, METAR reports. |

|

Examination of Some Coastal Stations Wind and pressure conditions are plotted for Quillayute and Astoria in Figures 7 and 8, below. Conditions were dramatically different between the two observation sites. Astoria experienced a long period of southerly winds which quickly escalated to 25 to 35 mph with gusts of 50 to 60 as the barometer began to climb. Quillayute underwent a brief period of southeast to south winds which could barely manage 10 to 15 mph with gusts of 15 to 30 at the bottom of the pressure curve. These southerly winds died down as the pressure began to climb. Not shown on the meteograms, the temperature at Astoria climbed from 39 F at 23:29 HRS on the 26th to 56 F by 02:55 on the 27th during the maximum southerly winds, while at Quillayute it escalated from a low of 37 F at 23:53 HRS on the 26th to 49 F by 08:53 HRS on the 27th. Heavy rain accompanied the southerly winds at Quillayute, amounting to 0.19" between 06:53 and 07:53, strongly suggesting that the storm's leading occlusion was to blame for the southerly winds. Astoria, being further south, appears to have been south of the triple-point, and experienced the classic warm-front cold-front scenario outlined in the Norwegian model of cyclogenesis. In other words, Quillayute got a brief diluted taste of the warm air racing northward around the east side of the storm before the center made landfall around 10:00. Landfall, with the storm's center just south of Quillayute, is marked by the brief period of low wind between 08:53 and 09:53. The barometer started rising before this, suggesting that the low had already begun to weaken from terrain interference even before it made landfall. The 10:53 time period is marked by a sudden escalation of west-northwest winds to sustained values of 20 mph gusting to 28. A pressure surge of about 0.12" per hour for two consecutive hours accompanied this wind, and the temperature fell back to 39 F by 11:00. Quillayute was overrun by the cyclone's bent-back occlusion. Astoria's wind shifted to nearly westerly by 10:55, and this continued up to 12:55 with a lowering of temperature to 45 F by 11:55, all the mark of the storm's trailing cold front. Source: Hourly data are from the National Weather Service, Portland and Seattle offices, METAR reports. |

|

Wind Measurements at My Home in East Portland A Maximum Vigilant anemometer with a Nor'Easter set as a repeater was used to take wind readings at my home. The sensor is about 26 feet above ground level, with a 250 foot site elevation. The methodology was simple: During a 4-minute observation window starting at the time of record, a set of 20 consecutive Nor'Easter readings were noted, usually during minute one to two, to calculate a single 1-minute average. The Nor'Easter samples every 3.4 seconds, so an average of 20 samples is actually a [(20-1)*3.4] 64.6-second value. Peak gusts on the Vigilant were also noted for the 4-minute period, as well as temperature, pressure, cloud and rain condtions. Between the main observation times, which were typically done each half hour, the Vigilant was monitored nearly continuously, with all gusts of 30 mph or more, and their times, noted. There was no attempt to calculate 1-minute averages between the main observations. Since many of the highest gusts occurred outside the regular obs, the highest 1-minute speeds were not masured. One-minute winds probably reached 22 to 25 mph during times of sustained 30-35 mph gusts, which sometimes lasted 5 to 10 seconds. Wind direction was determined by observing a string--tied to the anemometer mast at 23'--during a brisk wind period, and by the sway of nearby trees. In Table 1, below, the format is similar to the NWS x G y P z notation, with x being the 1-minute wind (NWS 2-minute), y being the peak instant gust in the 4-minute window (NWS peak 5-second gust in a 10-minute window) and z being the peak gust since the last observation. Winds tend to be particularly gusty at this location, especially when compared to the official sensors located among the open runways of airports. Mt. Tabor, who's peak is to the south-southeast, and who's forested western shoulder stretches out to the south, probably accounts for some of the turbulence, as do local trees, homes, powerlines and businesses. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A Look at the Forecasts The NWS forecast for the Portland area as early as 09:40 on December 26, 2002 was for winds of 20 to 30 mph with gusts to 45 by the morning of the 27th, almost 24 hours ahead of the actual event. I'd say this excellent job of forecasting verified quite nicely at my home. As did the forecasts for many areas of the Pacific Northwest for this storm. What follows is a brief look at some of the National Weather Service forecast discussions about the December 27, 2002 storm. These were collected from the Portland and Seattle offices as the storm progressed. For the sake of brevity, material that wasn't directly related to the cyclone's development has been cut from these forecasts.

The above prognostication shows awareness of the storm's threat, with an uncertainty about the exact storm track that would persist for some time. This is even more evident in the analysis from Seattle:

The tracks for the computer-model low were all over the Washington coast. In a general sense, the models were producing reasonable depictions of events on December 27, 2002, with a low moving onto the Washington coast. But the fine details of storm track can make a big difference for specific forecast regions. A low tracking over Astoria would mean much lower winds on the South Washington Coast compared to a low tracking across Quillayute. The southern track would tend to spare places like Long Beach and Hoquiam from damaging winds. The northern track would leave the two locations exposed to the low's southern side, the zone of highest risk for damaging winds during these cyclone events. Thus the reluctance to jump on a wind warning for the Washington Coast at this time. The Portland forecasters were in a better position, as the models were showing the storm moving north of Oregon, allowing for better confidence in issuing coastal warnings.

The mid-morning Seattle discussion doesn't show much change in the uncertainty for the Washington forecasters, though a track into Southern Vancouver Island was favored, and the extreme southern track suggested by the Canadian model was thrown away.

During the afternoon of the 26th, the exact strength of the low was becoming a bigger issue than track, as a wave on the storm's frontal system threatened to sap some of the energy from the lead storm. Oregon, assuming a track into Southern Vancouver Island, would be on the periphery of the storm's strongest gradients. A deeper low could put Oregon under a stronger gradient situation, which could make the difference for high winds being limited just to the coast, or having broader coverage into the Coast Range. A really big storm moving on the Southern Vancouver Island track could even bring damaging wind to the Willamette Valley, but in the case of the December 27th low, this had been determined to be unlikely.

In the Seattle Area Forecast Discussion, the MM5/MESOETA model struck gold, as thie actual path of the December 27th storm was very close to the one suggested during this model run. Of course, the forecasters didn't know that this MM5's track was close to the eventual real one, and the synopsis still suggests that the low would pass over Cape Flattery and into Southern Vancouver Island.

During the night, conditions at offshore buoys and coastal stations all pointed toward the cyclone moving into Washington's Olympic Peninsula as the models advertised, lending confidence to the wind forecasts. As supported by the Seattle forecast:

The timing of the high wind period for Seattle in the above discussion would pretty much verify. Seattle's strongest winds occurred right around noon, with light winds in the 04:00 to 07:00 PST (12Z-15Z) time frame when the cyclone was due west. So, 12-15 hours before the actual gale event, forecasters in Portland and Seattle had pretty much worked out the scenario and issued wind forecasts that would pretty much verify. Which led to:

There were two regions covered by this high wind warning where the heavy winds did not occur. Washington's Southwest Interior, including Kelso, Chehalis and Olympia, experienced peak wind gusts in the 30 to 40 mph range. This despite the fact that nearby places such as Shelton, with a peak of 47 mph, and Tacoma, with a peak of 51 mph, had gusts more in line with the forecast. The lack of high winds in this region is hard to explain when gusts across the Willamette Valley were equally as high, if not higher, and just to the north, in the Puget Sound region, the high wind warning fully verified. The other region missed by this cyclone's gale winds was Washington's Northwest Interior, including Bellingham, Friday Harbor, Port Townsend, Port Angeles and Sequim. These places appear to have had peak gusts in the 20 to 35 mph range, due to the fact that the low tracked just south the region. This exemplifies the difficulties in wind forecasting--a track difference of just 25 miles either north or south would have altered conditions enough to have changed the actual results, putting new areas under the gun, and sparing others. Overall, despite the nitpicks, the forecast in the 30 hours leading up to the storm were clearly well done. |

General Storm Data Table 2, below, lists the barometric minimums for the December 27, 2002 storm at selected sites. Many Pacific Northwest windstorms have produced lower readings. The most depressed pressures during this storm were near the Washington shore, and included 29.22" at 07:00 at Buoy 46041 near Cape Elizabeth, and 29.24" at Destruction Island from 05:00 to 07:00. Sources: National Weather Service, Eureka, Portland and Seattle offices, METAR reports, and the National Data Buoy Center, realitime meteorological data. |

|

Table 3, below, lists the maximum gradients for some standard measures during the December 27, 2002 cyclone. Compared to big storms in the past, none of these readings are particularly extreme. The PDX-SEA measure of +10.7 mb approached some of the more extreme values in history, but still fell short of storms such as January 20, 1993 with an astounding +15.4 at 10:00, January 16-17, 1986 with +11.7 at 00:00 HRS, November 24, 1983 with +12.6 at 12:00 HRS, December 14, 1977 with +12.3 at 17:00 HRS, March 25-26, 1971 with +11.1 at 11:00 HRS, and November 3, 1958 with a strong +13.6 at 20:00 HRS. The December 27, 2002 storm did, however, exceed the November 15, 1981 storm, which produced a peak PDX-SEA gradient of +9.7 at 15:00 HRS, and the major windstorm of November 13-14, 1981, which produced a peak of just +10.4 mb due to the storm center's distance offshore. Other storms that weren't quite at the level of the December 27, 2002 event include February 12-13, 1979 with a peak PDX-SEA gradient of +7.9 mb at 01:00 HRS, January 19-20, 1964 with +7.2 at 17:00 HRS, and even October 12, 1962 with +9.9 at 20:0--the latter probably for reasons similar to November 13-14, 1981. Sources: National Weather Service, Eureka, Portland and Seattle offices, METAR reports, the National Data Buoy Center, realitime meteorological data, and the National Climatic Data Center, unedited surface observation forms (for historical storm pressure data). |

|

Another measure for storms that track across the Olympic Peninsula and/or South Vancouver Island is the longer PDX-BLI gradient. Table 4, below, ranks a number of memorable, and not-so-memorable, storms by this measure. The December 27, 2002 storm ranks a meager 14th place in this incomplete list of windstorms from 1934 to present. Some of this has to do with the fact that the storm's center tracked south of Bellingham, which probably had a reducing effect on the peak gradient. The PDX-BLI gradient might have reached +13 to +14 mb if the track had been more ideal, with the low center passing right over Bellingham. The +22.7 mb for the October 21, 1934 storm was taken from spotty pressure data, and could have been higher--the mark of one of the top most powerful storms of the 20th century. Sources: National Weather Service, Eureka, Portland and Seattle offices, METAR reports, and the National Climatic Data Center, unedited surface observation forms (for historical storm pressure data). |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 5, below, lists the peak wind and gust for eleven key stations in the Pacific Northwest, their direction, and their time of occurrence. "Peak Wind" is a 2-minute average, and "Peak Gust" is a 5-second average. By my own personal methodology, a wind event rates the term "windstorm" when the average peak gust of these eleven stations reaches 39.0 mph (gale force) or higher. The December 27, 2002 cyclone just barely made the cut, and is a minor windstorm. Moderate windstorms have an average of 45.0 to 54.9, and major windstorms are those that reach or exceed 55.0. Only a handful of storms have made the majors, including December 12, 1995, November 14, 1981 and October 12, 1962. Bellingham was the big loser during the December 27, 2002 wind event. The highest gusts occurred with the pre-storm northeasterlies five hours before the cyclone made landfall. Sea-Tac stands out strongly among the interior stations for top winds, and the Oregon Coast clearly took the brunt of the storm. Interestingly, the averages for this event are almost exactly one-half of the average 49.7 mph 1-minute wind and 80.5 peak instant gust velocities achieved by the for the Columbus Day Storm. The Big Blow of 1962, on average, struck with about four times the force! Note, however, that the newer 5-second gust adopted by the NWS muddies the kind of comparison that I describe here. See "Adjustments to Modern Storms." Sources: National Weather Service, Eureka, Portland and Seattle offices, METAR reports. |

| Location | Peak |

Direction |

Obs Time of |

Peak |

Direction |

Obs Time of |

| California: | ||||||

| Arcata | 17 |

160 |

23:53 HRS, 26th |

32 |

160 |

23:53 HRS, 26th |

| Oregon: | ||||||

| North Bend | 41 |

190 |

03:55 HRS, 27th |

61 |

190 |

01:35 HRS, 27th |

| Astoria | 37 |

190 |

06:55 HRS, 27th |

59 |

190 |

06:55 HRS, 27th |

| Medford | 20 |

150 |

17:43 HRS, 26th |

30 |

160 |

22:53 HRS, 26th |

| Eugene | 28 |

220 |

07:54 HRS, 27th |

39 |

220 |

07:54 HRS, 27th |

| Salem | 25 |

210 |

05:33 HRS, 27th |

37 |

200 |

05:56 HRS, 27th |

| Portland | 25 |

210 |

09:55 HRS, 27th |

39 |

210 |

07:55 HRS, 27th |

| Washington: | ||||||

| Quillayute | 20 |

300 |

10:53 HRS, 27th |

32 |

310 |

11:00 HRS, 27th |

| Olympia | 25 |

240 |

12:22 HRS, 27th |

40 |

190 |

11:21 HRS, 27th |

| Sea-Tac | 32 |

220 |

13:56 HRS, 27th |

52 |

200 |

11:56 HRS, 27th |

| Bellingham | 14 |

030 |

04:53 HRS, 27th |

22 |

030 |

04:53 HRS, 27th |

| AVERAGE | 25.8 |

193 |

40.3 |

187 |

References [1] Information for this sentence, and those following, is from "Winds roar over region, toppling trees," Oregonian, December 28, 2002, Metro/NW, pages E1 and E6. [2] Information in this paragraph is from the Seattle Times article, "Windstorm whips region: 10-year-old killed; gusts litter area with debris," from the newspaper's online archives. |

Last Modified: March 19, 2004 You can reach Wolf via e-mail by clicking here. | Back | |