The January 9, 1880 "Storm King" compiled by Wolf Read |

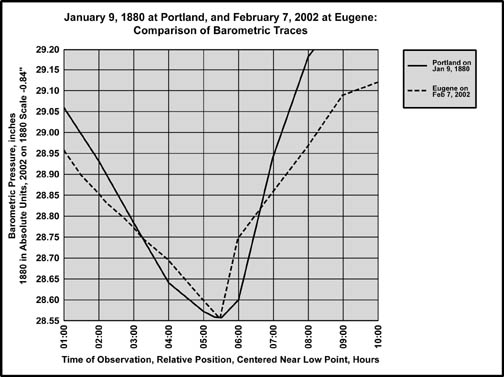

"Blowdown" is sometimes used as a term for record northwest windstorms, as pointed out by Kruckeburg is his wonderful book, "The Natural History of Puget Sound Country" [1]. A "blowdown," roughly speaking, appears to be a storm that knocks over 1 billion or more board feet of timber, and sometimes more than 10 billion [Footnote 1]. By this definition, Columbus Day 1962 was the last major "blowdown" to date, having thrown about 11 to 15 billion board feet of timber [2]. Three others occurred in the 20th century: January 29, 1921 with the loss of about 8 billion board feet mostly in Washington, October 21, 1934, and December 4, 1951 which toppled about 9 billion board feet mostly in Oregon [3]. Anecdotal evidence suggests at least one for the late 19th century, on January 9, 1880. From the information gathered for this website, the large windstorms of November 14, 1981 and December 12, 1995 apparently did not fell 1 billion or more board feet of timber, and thus do not make the list of the truly great windstorms of history. The timber loss from the two late 20th-century storms seems to be in the range of millions, maybe tens of millions, of board feet. As of 2002, the May 18, 1980 eruption of Mt. St. Helens is the last natural calamity to topple enough timber for blowdown status in the Pacific Northwest [4]--the lateral blast from that event could be considered as a kind of windstorm, but volcanic eruptions are outside the scope of this website. Calculating from the few available datapoints, it seems that major blowdowns are roughly a thirty to forty year event. January 9, 1880: A Most Unusual Storm If cyclones competed for "Strongest Storm on Record," the final round would probably be between the windstorm of January 9, 1880, and the Columbus Day storm of 1962. Due to limited wind data in 1880, this assessment is based primarily on anecdotal evidence presented in newspapers, such as the Daily Oregonian, and from what weather observations could be had from carefully monitored stations like those of the U.S. Army Signal Service. If the articles are taken at face value, then it seems that damage in 1880, at least to timberland and orchard trees, was comparable to the Columbus Day Storm. On January 9, 1880, an extremely deep low--possibly deeper than 955 mb--dove inland near the mouth of the Columbia River, probably south of Astoria, on a track that was apparently in a northeastward direction that skirted across Washington County, and then through the Kalama area. This path is based on noting areas that had little or no damage, which contrast sharply against reports of severe damage in regions nearby, and is critical in understanding the nature of a specific type of windstorm: those produced when strong lows move inland. The "Big Three" examined in detail on other pages, October 1962, November 1981, and December 1995, stayed offshore during most of their high-wind generating period, in some cases fairly far offshore. When a midlatitude cyclone moves overland, instead of following the coastline, it creates a signature that is distinct from the Big Three, mainly because places north of the low's centerline tend to be spared the highest winds, and also because the same locations sometimes experience snow from the low's cold northwest quadrant. The "South Valley Surprise" of February 7, 2002, is in this category of landfalling lows. The January 9, 1880 storm is possibly the most extreme example in Pacific Northwest weather history. The reader is encouraged to compare the 1880 storm with the 2002 event and note the similarities in overall pattern. In the recent storm, the climatological signatures are weaker; they are still evident enough, however, and with a great amount detail available in the modern era of weather record, the February 2002 windstorm serves as a good model for understanding the powerful storm of 1880. Another tempest from Washington's colorful history, a compact cyclone that rolled ashore right over Hoquiam on November 3, 1958, adds some more details for interpreting the 1880 storm. On its way inland, the low passed just north of Olympia, giving Washington's capitol a southerly blast nearly equal in strength to the Columbus Day "Big Blow" that would occur just four years later, and moved just south of Sea-Tac Airport, kicking up a northwesterly gale unparalleled in the airfield's history, and providing a nice clue about the path of the 1880 storm. Two windstorms from the 1960s--March 27, 1963, and October 2, 1967--add even more information. It seems that the 1967 storm most closely matches the 1880 cyclone in its wind effects on the region. Finally, an event on March 1, 1974 may offer some clues about the larger, synoptic situation that may have produced the 1880 windstorm. On January 19, 1880 a letter to The Daily Oregonian (hereafter referred to as just the Oregonian) from Astoria reads, "From the graphic, and, in some cases, the heart-rending accounts published in the Oregonian descriptive of the disasters resulting from the late severe windstorms in other portions of the state and the neighboring territory, it would appear that our town and county suffered less injury than almost any other" [5]. The lower Columbia was also spared, as evident in this report from January 12th, "The storm near the mouth of the Columbia seems to have been entirely distinct from the one which swept through the Willamette valley, and scarcely as severe or prolonged. The wind was from the northwest, and did not commence to blow violently until nearly 2 o'clock Friday afternoon." In contrast, a letter from Newport, far to the south, reported, "We have just experienced one of the severest gales; nothing like it has occurred since the settlement of the bay. It was southeast, lasted about five hours, and was terrible in force . . . The tide rose seven feet higher than was ever known; nearly all the old wharves are taken away." There was no snowfall on the coastal hills around Newport, but "several miles from here it is five inches, and gradually deepens as you go east. Said to be 18 inches deep at Siletz." Further south, Gardiner was struck with a "perfect gale" that threw large breakers ashore and shoved water into a warehouse, threatening livestock. "The rain came down in torrents," and the Umpqua and Smith rivers flooded high, adding to the wet mess. "The storm raged with great violence at Coos Bay," noted the Oregonian. The three-masted schooner Emma Utter dragged anchor and was smashed ashore. Inland, in Washington County, Forest Grove reported no damage. And from Hillsboro, "The storm of Friday in all its mad fury did not seem to reach the western portion of our county, but seemed to abate from rock creek." Whereas in Clackamas County, the Oregon City Enterprise reported, "Vast quantities of trees have been torn up by the roots--in many places whole groves. This county, compared to its former condition, is comparatively open now." From Sheridan comes this neat bit of information, "The wind in the morning was blowing briskly from the southeast, but soon it shifted to the southwest, and then promenaded all around the circle and back to the west. At about fifteen minutes to seven o'clock the regular gale commenced with a velocity of fifty to fifty-five miles per hour. The main current appeared to follow the course of the Yamhill River . . ." A bit further north, in the Carlton area, there's a nice observation: "The wind first came from the south tearing down all the east and west [fence] lines; then changing to the west it flattened all the north and south lines." Benton, Linn and Yamhill Counties suffered heavy loss, though it was reported from Corvallis that damage in the vicinity didn't seem to be as great as places north. In Marion County, winds raged for four hours, and the roof of the State House in Salem was damaged. As the winds faded, snow started sifting down [6]. The following day, seven inches adorned the capitol grounds in a peaceful display that seemed to deny the previous gale. Further south, in Lane County, Eugene reported little or no damage, and had four to five inches of snow. To the north, along the Columbia River at Westport, came this report: "On the 9th at 2 o-clock P.M., a storm of snow and wind set in and continued for two hours with all the fury of a hurricane." And "the heaviest windstorm ever known in these parts" struck Monmouth, in Polk County, at about 11 A.M. The strong winds also struck the city of Corvallis at 11 A.M, with the gale lasting until about 3 P.M, and started around 9 A.M in Blodgett in the coast range to the west. In Washington County, the powerful wind began at 11 A.M., and lasted until about 2:30 P.M. The United States Army Signal Service operated a meteorological station in Portland. Many salient details about this storm were recorded, and then reported in the January 10, 1880 issue of the Oregonian. The barometric trace, which was corrected for temperature, altitude and instrumental error and reported to three significant figures, is particularly interesting. There's an astounding pressure drop, with an all-time record low minimum of 28.556", and then a powerful rise, in a narrow range of time. In an article titled, "The Storm," which also appeared on January 10th, it is reported that, "The sudden and rapid falling of the barometer indicated a really fearful storm, and we are informed that such a declension of the mercury in the states east of the Rocky Mountains would have been regarded as a harbinger of a hurricane that but few if any buildings in Portland could have withstood." Later, the article goes on to say that examination of examples in the Sailor's Handbook, an authoritative source from the era, failed to produce "a greater depression of the mercury in the same space of time on land than was witnessed here yesterday." Figure 1, below, plots the barometric trace against the February 2002 south valley storm. With an extrapolated 0.34-0.37" an hour rise at Eugene, and a measured 0.33" at Corvallis, the 2002 event produced rates of pressure rise in the Willamette Valley that were greater than the infamous Columbus Day Storm of 1962 for any location [Footnote 2]. Figure 1, shows that on January 9, 1880, the barometer at Portland dropped faster than, and then rose with nearly an equivalent slope to, the 2002 storm at Eugene. The 1880 cyclone appears to have produced the most extreme barometric trace in the weather record of Oregon. Only the December 12, 1995 storm has produced a lower pressure in the state, with a reading of 28.53" at Astoria, but the rate of change produced by the recent storm wasn't even close to that experienced at Portland in 1880. |

|

| Figures 2 and 3, below, the pressure trace compared to wind speed and direction for Portland in 1880, and then Eugene in 2002, are critical to understanding just where the 1880 cyclone tracked across Oregon and Washington. As the barometers dropped toward the low points for the prospective storms, winds picked up from the southeast. Then, as the pressure traces bottomed out and began to climb, winds became southerly and reached peak velocities. It was noted by the Signal Service meteorologist at Portland that the wind jumped from an average of 4 to 5 mph to 39 mph in just 15 minutes between 11:00 and 11:15 AM, a remarkably fast acceleration that agrees well with the sudden onslaught of wind at Eugene in 2002. A western component to the wind direction arrived along with the fastest rise of the barometers. Winds decreased from this point onward. The similarity in conditions between the two locations suggests that each station was in a similar position relative to their prospective storms. In 2002, the low center tracked about 25 miles north of Eugene; and in 1880, the cyclone probably tracked a similar distance north of Portland. |

|

To the south, Oakland, Oregon, had an "unusual amount of snow." The road from Roseburg to Coos Bay had up to five feet, and many trees along the route had been toppled by the wind, making horse travel impossible. Moving northward, a report to the Oregonian from the Vancouver Independent in Clarke County, Washington Territory [7], said, "The damage to timber in Clarke County is immense and seemingly beyond computation . . . fully 50 per cent of the trees fit for lumber are in windfalls . . . not less than 25 percent of all timber in Clarke county is blown down . . ." According to a report from Kalama, the community was struck by rain mixed with snow, and a "fierce gale of wind" from 2 PM to 4 PM, which produced timber blowdown, two large landslides, and little structural damage save for the loss of a few old sheds. In the Fort Clatsop area along the Lewis and Clark river, it was reported that, "The wind changed suddenly to the west, and while the trees were heavily laden with snow, struck the forest with terrific effect." Seattle reported no wind-related damage, even though the barometer fell as low as 28.41" at Port Townsend to the north. The entire Puget Lowlands was spared a severe blow, but suffered a tremendous snowstorm instead. The January 9th cyclone produced the second big snow event for the region in the space of two days, with near-record short-duration accumulations that included about two feet in areas around Seattle. A deeper snow fell in a storm on January 7th and 8th, an event that produced accumulations of two to four feet around Seattle and Port Townsend, gave Astoria a strong gale along with the highest tides in 13 years, caused severe blowdowns in the Fort Clatsop area, and dropped Portland's barometer to 29.19". The report from Kalama quoted above, which was written on January 10th, mentioned four inches of snow on the ground there, two to three feet between Winlock and Tenino, and three to five feet between Tenino and Tacoma. According to the Kalama train that arrived on the 11th, the snow at Tacoma was 35 inches deep early Friday, and this figure had jumped to 54 inches by Monday afternoon. Snow loading caused problems all over the affected region. Olympia reported severe damage to structures. Sheds and barns collapsed at Port Townsend. In Seattle, on the 8th, flakes accumulated at the rate of 1.5" an hour with temperatures just above freezing, making for a heavy, wet blanket. The weight of the snow base had reached 52 pounds per square foot, causing roofs to fail; with four feet "on the level," it was said to be the heaviest snowfall since at least 1852. Telegraph lines between Seattle and Portland were down, as were those around Port Townsend. With all modes of land travel impeded by the deep white barrier, and shipping hindered by high winds and surf in places, communication with outside regions was very slow at best. The storm track depicted in Figure 4, below, along with notations of the storm's effects, is an interpretation based on the descriptions reported above. Figure 5, also below, compares the path of the 1880 cyclone with that of the 2002 south valley windstorm, and the October 2, 1967 event. Note that the track that I have inferred is different from other interpretations (more on this below). |

|

The close correlation in weather conditions between the 1880 and 2002 storms, with strong wind effects reaching into the north Willamette Valley in 1880, suggests a path somewhat north of the 2002 cyclone. It seems that the motion of the 1880 low was strongly northeast, with a landfall probably in the vicinity of Newport. The heavy rain and flooding rivers reported at Gardiner, to the south of Newport, appear to be the product of the warm air advection that is a standard feature for the southeast quadrant of Pacific lows. Some of the flooding may have been due to snowmelt before the onset of colder air, which arrived with the bent-back occlusion that almost certainly reached deep into the low's southwest side. The southeast gale, waterfront damage, and snow-barren coastal hills at Newport suggest the low center passed very close to this location, if just to the south (see the data graph for North Bend for the February 2002 event). The storm then cut inland, moved along the border of Lincoln and Yamhill counties, almost over Sheridan (suggested by the wildly shifting wind direction), passed just north of Carlton (suggested by the strong southerly winds at the beginning of the storm), and through the center of Washington County, south and then east of Forest Grove, sparing the small community any damage. Judging by the sudden onset of strong winds in the Willamette Valley around 11 A.M. from Corvallis to Hillsboro, the low center had probably crossed over land by this time, producing an array of tightly-packed south-to-north-stacked isobars up the valley. Though it must be noted that the early onset of strong winds at Sheridan, around 7 AM, is difficult to explain with this assertion--there could be unique features of terrain, like the valley of the Yamhill, that helped initiate the west winds sooner here than at other locations. I've heard anecdotal evidence from residents of the east Coast Range drainages that strong south winds in the Willamette Valley can create damaging west winds in the mountains' east-west trending valleys. The northerly airflow in the larger Willamette Valley apparently pulls air out of the little basins, creating locally strong west flow. The disparity, however, is so great, even in reference to the 9 AM arrival of the winds at Blodgett in the coast range, that the reported time may simply be in error. One last possible explanation for the time disparity is that Sheridan may have been just north of the low's center, and was not subjected to the January 9th cyclone's high winds, and that the report is about the event that occurred on January 7th and 8th. Getting back on track, the barometric trace at Portland suggests that the cyclone's eye passed over Washington County between 12 and 2 PM, which is also the period of highest winds for the Portland Metro area. The storm then crossed the Columbia River northwest of Vancouver, Washington Territory, then shot north of the city, but stayed far south of Olympia, probably even south of Kalama. The light damage report from Eugene at the south end of the Willamette Valley, compared to heavier damage from Benton County north, suggests that the strongest pressure gradient around the low center dragged across the valley between Corvallis and Vancouver. Places along the northwest coast of Oregon, and the southwest coast of Washington Territory, probably received a fairly good north to west blow as the low's hypothetical bent-back occlusion dragged through. The late arrival of winds at Westport--2 PM--with the onset of snow suggests the arrival of the bent-back occlusion, and that it moved in with a fair amount of violence. The report of northwest winds from the mouth of the Columbia River, peaking at 2 PM, and at Kalama from 2 to 4 PM, strongly corroborates this. Westerly winds by 3 PM put a bent-back arrival time by that hour for Portland. Examination of the METAR plots available for the February 2002 storm at Newport, and north Willamette Valley stations, show the basis for these conclusions. Newport is shown in Figure 7, below. Note the sudden shift of wind to a northwesterly direction, the mark of a low center passing to the south of the station, and then the escalation of winds shortly after, as the bent-back occlusion arrives at the site (marked by a drop in temperature). In 2002, Corvallis had a sudden burst of west wind into the mid 40-mph range at the arrival of the bent-back on the low's immediate west side; with the 1880 low being more intense, places like Kalama and Westport, which are suspected of falling under a similar region of the earlier cyclone, probably experienced higher winds. Corroborating the idea of higher winds along 1880 bent-back occlusion is the November 3, 1958 cyclone. When the 1958 storm's center passed just south of, and then to the east, of the Seattle-Tacoma Airport, it kicked up a sudden northwesterly gale of 39 mph gusting to 59. Considering the dramatic difference in strength between the 1880 and 1958 lows, the bent-back occlusion in the 1880 storm could have easily thrown gusts of 60 mph or more in areas immediately to the northwest of the storm center. The bent-back occlusion, wrapping around the backside of the low, appears to have pulled snow-refrigerated air from Western Washington and yanked it southward across Oregon. This likely contributed to the lowland snowfall evident in reports along the Coast Range, and at Eugene and Salem. For these southern locations, the bent-back performed like a cold front. Its passage was marked by a sudden shift in wind direction from south to west, and a chilling drop in temperature.

George Miller, a retired National Weather Service professional, in his excellent book, "Pacific Northwest Weather," (Frank Amato Pulications, 2002) suggests a track straight in out of the west, with the low passing just north of Astoria. He mentions that the barometer fell to 28.45" at Astoria, the lowest ever recorded in Oregon. This interpretation motivated me to go right to the source, and obtained some photocopies of the relevant section of the January 1880 Monthly Weather Review from some very helpful people at the Library of Congress. Figure 6, below, is a scan of the storm track map for January 1880--the track of interest is labeled VI, or the sixth cyclone of the month to affect the United States. The map strongly supports my interpretation for the storm's track. It is interesting that the cyclone that arrived just two days before the January 9th cyclone, depression V, followed a track more in line with Miller's interpretation.

|

In regards to the track in Figure 6, of particular interest are two reports from vessels of the Pacific Mail Steam Ship Company. It is fortunate that these two ships were in a good position for collecting data on this storm, and that they both survived what was one of the most intense cyclones to have ever landed in Oregon. While off the Umpqua River (near Winchester Bay), the Oregon reported an incredibly low barometer of 28.20" (955 mb!) at 6:00 AM, a level that was maintained until 10:00 AM. At that time, a heavy sea whipped up by a strong SE wind tore off part of the ship's bulwarks, and the barometer began rising. The SE winds continued until noon, when it switched to the SW, typical directions for a location south of the storm's center. The Victoria, located about 45 to 50 miles northwest of the Oregon, also showed a low barometer of 28.20", but had NW winds--a directon that puts the Victoria north of the storm's track. Indeed, it appears that the cyclone moved right between the two steamers! The data from these ships pretty clearly fixes a southwest origination for this low, which makes the associated snowfall even more amazing! Also, 28.20" is a lower reading than the minimum of 28.30" (958 mb) recorded for the great Columbus Day Storm. And it is possible that the actual central pressure was lower than the readings obtained by the two steam ships, as the storm appears to have tracked between the vessels. A minimum central pressure of 28.10" (952 mb) isn't out of the question, and it could have been lower if the low had a compact core. In other words, this low may have not only outclassed the greatest extratropical windstorm of the 20th century in the United States (despite what some Easterners may believe, the March 1993 "superstorm" doesn't hold up to the Columbus Day Storm's maximum winds--it takes a strong hurricane to compete with the tempest of 1962), but the January 9, 1880 cyclone may have been deeper than the 953 mb December 12, 1995 cyclone that landed on Washington's Olympic Peninsula. This serves to emphasize the remarkable nature of the 1880 cyclone. According to the Monthly Weather Review report, Olympia reported a low barometer of about 28.49" (adjusted by me to sea level) at 2:00 PM, which is lower than Portland's 28.56" at 1:20 PM. This suggests that the cyclone's center may have passed more closely to Olympia than Portland, which would mean that my maps are somewhat in error, though the track was still south of Washington's capital. At New Westminster, British Columbia, the barometer fell to about 28.69" by 3:00 PM, which also supports the southerly track of the low. South of Portland, Roseburg shows a low barometer of about 28.79" occurring in classic double-dip fashion first at 7:55 AM and then again at 11:55 AM--though not as spectacularly deep as places north, this is an incredibly low reading for Roseburg. The timing of the minima also support the idea that the cyclone moved in out of the Southwest. |

The Storm King's Wrath Newspaper reporting of natural events in the 19th century was detailed in a way that has all but vanished today [Footnote 3], and many more facts about this major windstorm can be gleaned from the Oregonian. On January 17th these observations from Washington County appeared: 500 to 600 trees were thrown across the railroad track between Beaverton and Hillsboro, while only 16 fell on the stretch between Cornelius and Hillsboro. As areas south of a storm center typically experience the highest winds, this information also suggests that the low tracked north of Beaverton, while staying south of, or passing right over, Cornelius. But the information is of limited value. The highest winds were reported out of the southwest at Hillsboro, and allowing for the direction of the rail lines, east-west for Beaverton to Hillsboro, and southwest-northeast for Hillsboro to Cornelius, a large part of this disparity may be accounted for. Also, the tree density along the two lines is not noted, further reducing the value of the information. A report from Clackamas County, on January 19th, 1880, mentions 225 trees down on one mile of road near Canemah. That's an average of one tree every 23 feet! From Linn's Mill to Oregon City, a distance of about seven miles, 349 trees lay across the road, an average of a tree every 105 feet. One 300-foot portion of the span had 19 boles prostrated across it, making for an average of one tree toppled every 15 feet. This data can be used to calculate a rough blowdown rate for the three figures. If the average timber height is 160-180 feet, meaning that trees have to be within about 160 feet to reach the road when they fall, and there's an average separation of 10 feet between trees (very dense!), these blowdown percentages result: 1 tree per 15 feet of road, 6.2%; 1 tree per 25 feet of road, 3.1%, and 1 tree per 105 feet of road, 1.0%. If tree separation is wider, say 20 feet between boles, then the percentages jump to 25.0%, 12.5% and 2.5% respectively. The peak rate, 19 trees across 300 feet of road, probably represents a blowdown of 6% to 25% by this rough calculation. Note that the bigger percentage corresponds closely to the timber loss reported in Clarke County, just to the north. The calculation assumes dense timber along the entire length of the respective roads, which probably was not the case (which would push the blowdown rates higher). And the average height of the forests could have been less in many locations. Also, even a 1.0% percent windfall rate, which represents about 500-2,000 trees down per square mile when using the above densities, when summed across the thousands of square miles afflicted by this storm, represents the loss of millions of trees. Conditions were worse in some locations, lighter in others. According to the January 12th, 1880 Oregonian, in the Portland area, "near J. W. Kern's place," 300 yards of one road was buried by 65 trees, making for an average of one tree per 13 feet. Nearby, over a quarter mile, some 200 trees were toppled, an average of one tree per 6 feet. No less than six trees fell across Mr. Kern's barn! Twenty-one trees landed on the track between Oregon City and Portland, a north-south line. A six-mile stretch of road between Portland and Washington County had a 287-tree blockade, an average of one tree per 110 feet. And 365 trees fell across the west side track between Portland and Beaverton, a run of about 15 miles that yields an average of one tree per 216 feet. Other evidence of terrific tree damage comes from reports like, "The place now owned by C. Albright, known as the M. Mann place, had nearly all the timber blown down . . ." [8], "At Damascus, half of the timber is down," and in the Santiam area, "after the storm, the river was so full of floating logs that he [John Shea] could have crossed on them." The Dallas Itemizer mentioned to the Oregonian, Jan 17th, "The storm blew down . . . three large fir trees across the road near the rocky branch and nearly all the large fir, ash and maple trees on the island opposite Eola, and at least one thousand trees in hearing distance on the river bottom, obstructing all the roads thereon." Also from Yamhill county, in the Amity area, "trees were torn up by the roots and hurled about in all directions." This may sound like wild, hyped-up news-writing, until the report of south winds shifting to west from Carlton (just to the north of Amity) is considered: With trees first falling in a northward direction, and later toward the east, crossing over each other, the forests probably looked like chaos at its finest. At Salem, which escaped the terrible destruction that visited the valley just to the north, it was mentioned, "The damage to shade trees and shrubbery in this city is not inconsiderable by any means, and almost any property owner in this neighborhood will lose something." In southern Clackamas County, on J. W. Roots' 200-acres of timbered land, "not more that four trees out of 100 were left upright. The region around Roots' land was so disfigured that he wasn't sure he could find his way home. In Multnomah County, it is written that only "one or two small trees were left standing in the Talbot Grove." About four miles south of Portland, along Boone's Ferry Road, "Four-fifths of the timber between there and town is prostrated." A railroad engineer, who had to walk the seven-mile stretch of track from the south summit to Portland, and delivered a report to the Oregonian of 55 trees across the track between the two locations, also said, "that beyond the summit, the trees fell before the wind as wheat before a reaper." At Hubbard, a 30-year resident couldn't recall having ever seen, nor imagined, a storm capable of "completely leveling a grove of large fir trees of about 10 acres in extent, blowing scores of them down at one blast." A nearby apple orchard lost a third of its trees to breakage and uprooting. At Polk County, in Buena Vista, "The solid old firs that had withstood the storms of more than three centuries, finally had to succumb, and their falling so fast and so many sounded like a general upheaval of the forest." These notations, but a small selection of the many accounts of wholesale forest destruction, suggest that the estimations of blowdown percentage made earlier are probably low! And the last quote suggests a rough interval of three centuries for the magnitude of the wind event that struck in 1880. In the above coverage of tree loss, the catastrophe that befell the railroads in the northern Willamette Valley has been shown to a great degree. On top of tracks buried by trunk and branch, the train companies had other problems to contend with: the west side line in the Portland area had parts of bridges four and nine broken, though the damage was quickly repairable [9]. Eastside, a shed was blown down; damaged within was a directors' car and two new passenger cars. Several landslides added to the heavy track blockage from toppled trees. A falling tree narrowly missed an engineer as he headed northbound with an "empty engine" during the maelstrom. By January 12th, the railroad line between East Portland and Roseburg had been cleared of debris-it is mentioned that, because most trees fell northward, parallel to the track, damage was not as bad as it could have been, which allowed the line to be opened fairly quickly. Indeed, the heavy snows south of Albany were a larger problem for that particular railroad than the fallen trees. On the severely damaged west track, bridge nine had been repaired even sturdier than before by January 13th, and, with 20 crews working hard, it was expected that the regular "up train" from Portland would be running that afternoon. Considering the intensity of the storm at some locations, watercraft fared pretty well [10]. The steamboat Vancouver, despite her crew blasting whistle at the typical departure hour, was delayed by the wind until 4 o'clock. A stump roiling in the swollen Willamette River instantly snapped the cable of the Stark Street Ferry, causing delay from 11 AM to 5 PM. The steamer Bonita endured a "fearful windstorm" on her way up the lower Columbia River, with the greatest intensity between Rainier and Kalama. A steady snow fell during her entire trip. Despite the blizzard-like conditions, she arrived on time, and undamaged. On a trip down the Columbia from the Cascades, the Emma Hayward encountered a storm worthy of the deep ocean:

The O. S. N. and W. L. & T. Companies had two large fleets in Portland, stationed along wharves at the end of Washington Street and Morrison. Prudent action by Captain Geo J. Ainsworth, upon his seeing a startlingly depressed and steadily falling barometer, probably saved many ships stationed at the docks. He ordered all the idle vessels "put in the best possible condition to resist the storm." Even the old ships in the boneyard were secured. The result was not a single loss due to the storm, though a few ships tugged at their hawsers and chafed. Starting about 11:00 AM, heavy waves from the river struck the Eliza McNeil, a vessel lashed to the railroad wharf. The force of current and wave against the ship transmitted down her stern lines and upended the wharf's piles. Her stern swung out into the river. To prevent loss of her forward lashings, the bow anchors were dropped, and then, with great effort, the vessel held steady and weathered the storm. Portlanders initially assumed that Oregon's north coast had been ravaged by the storm just as severely as the valley, and feared that Astoria's shipping was devastated. They were surprised and elated to discover differently a few days later, when ships began to arrive from the lower Columbia. Among the worst to happen at Astoria: Alice lost her smokestack to the gale, the State of California smashed some pilings while trying to dock, and Wm. D. Seed dragged anchor and would have run aground if it wasn't for skillful handling by the mate in charge. On the lower Columbia near Brookfield, the Dixie Thomson, carrying 20 passengers on a regular run to Astoria, was struck with sudden violence by the storm's northwest gale [11]. She was nearly lifted from the water. The river, churned into a maelstrom by the wind, washed over Dixie Thomson's decks, and partially extinguished her boilers. Some breakers rolled the vessel nearly 45 degrees. Captain Pillsbury fought the elements for over an hour, using the new Gates apparatus, which had been shunned by river boaters for fear of being useless in heavy weather. In this case, the captain proved such notions wrong, and maintained good control of the boat. The gale began to subside, and it seemed that the worst was over, until a large log was spotted on a collision course. The forced avoidance crashed the ship's rudders against the shore, damaging them. Now, with only forward and backward capabilities, the captain fought to keep the vessel going in the violent storm. To the terror of her passengers, Dixie Thomson was thrown onto the mudflats with terrible force. This happened several times. The captain feared that the hull would fold with each crash. He maintained his well-known calm, and the vessel survived each brutal landing; eventually Captain Pillsbury was able to get the ship to steer free. He headed to the vicinity of Brookfield, and dropped anchor. The new location wasn't very safe, either, and a nervous wait ensued until the Elder, captained by Bolles, encountered the damaged vessel. A distress signal was sent, and Bolles acted immediately, fully aware of the risk, and managed to get close enough to send a line to Dixie Thomson. The line parted. A full ninety minutes of pummeling wave and wind passed before another lashing could be secured, at which time the Dixie Thomson was towed to safety at the port of Brookfield. After causing much worry as to its whereabouts, the steamer Idaho finally arrived at its destination in The Dalles Saturday night, some 25 hours late [12]. Among the people who passaged on Idaho, came dramatic accounts of the vessel's encounter with the Storm King. About a dozen passengers loaded up and left the Cascades around noon on Friday, headed east for The Dalles. Just ninety minutes later, the tempest pounced. Winds described as a hurricane caused Idaho to creak and groan, frightening the passengers, though one decided to go outside to see nature's fury first hand. He was blown onto his back and carried nearly the full length of the deck. Windows shattered, dishes fell, and the cabin supports broke. There was some fear that the cabin would be demolished, but Captain McNulty stayed at his post, and the crew worked furiously to keep the vessel alive. The stovepipe toppled, causing concern about a fire which did not occur. Not without difficulty, the boat was finally run aground on the lee side of an island that offered protection from the gale. There she stayed until the storm had abated. Returning to the plight of those on land, fences were so thoroughly flattened in some areas of the Willamette Valley, and other parts of Oregon, that they received strong mention in headlines: "Fences and Forests Laid Waste" (Clackamas County, January 19, 1880), "Fences and Bridges Alone Damaged to the Extent of $20,000" (Washington County, January 15th), and " 'No Fence' Law Triumphant" (Umatilla County, January 15th). After scanning many newspapers in the quest for information on later storms, never did fence damage turn up so prominently as it did in 1880. Some of this is probably the mark of the times and what was important to the 1880s reader. Broken fence reports were most likely replaced by snapped telephone and transmission lines as the population became increasingly urban and more "wired" over the ensuing decades. And broken fences probably became less of a concern to the majority as the automobile replaced the corralled horse. But there is also a signature of the wind strength in the fenceline damage. Near universality of destruction is almost always an indication that something significant had happened-in this case that the winds reached a level that most of the fences couldn't withstand. Or, when considering the time period, it could also mean that fence construction may not have been very sturdy in the 1880s. A note from Buena Vista in Polk County, that "the storm did not leave as much as fifty yards of plank or rail fence standing unbroken in the neighborhood," suggests the kind of fence that was vulnerable to the wind. Large wood planks would certainly catch the gusts better than the barbed-wire fences that are familiar in the countryside today. A comment on January 12th, from Roseburg, in which fence blowdowns happen "nearly every winter," also supports this idea that the kind of fences utilized at the time were prone to wind damage. Telegraphs, and their expanding cousin the telephone, which had been patented by Alexander Graham Bell just four years earlier [13], suffered the "Storm King". The Portland-area lines for the Northwest Telephone Company were disrupted, in some cases badly, but were put back in order within a few hours after the winds slowed [14]. However, the line between the central office and Springfield still remained dead on January 10th. As far as telegraphs went, a single small quote described things well: "The lines are down in every direction." In Portland, thirty lines were cut when part of the New Market Theater's roof was yanked off and tossed right into the wires above the Western Union Telegraph Company. "A large force of men" commenced repairs on the morning of the 10th, with high hopes of having the lines "soon in working order." The cable damage was great, and treefalls slowed down the transport of telegraph repair crews to the poles, which tended to follow the tracks. Even by the 12th, lines along the newly reopened railway south to Albany were still down and would require several more days for repair. The widespread telegraph blackout was no small matter for the newspaper, which typically received news via the system from all over the country. Communication with that important lumber consumer, California, and especially San Francisco, was shut down. News from significant places back east, like New York and Washington D.C., was missing. An overall feeling of isolation prevailed for many days as hand-carried letters and stories by word-of-mouth slowly trickled into the Portland area. On Monday, January 12th, 1880, under the large headline "Friday's Tempest," after a glowing account of the speed in which railroads were being cleared, it was written:

To briefly digress, almost exactly one hundred years later, citizens of the Pacific Northwest would be enthralled by the awakening of Mt. St. Helens, an event captured in full color and broadcast on television for the entire country to see. It was an event that far overshadowed any storm in 1980, and surely few people were worried about a gale that had afflicted the small populace that had lived in the Northwest a century in the past. Getting back to the century before, the beginning of the General News column on the front page of the January 13th, 1880, Oregonian explained the difficult communications situation fairly clearly:

The plight of the Kalama train demonstrates even further the communication problem wrought by the storm. Snow 30 inches deep buried the track at Tenino [15]. The powerful steam locomotive was powered up, and, as it pushed through the heavy white blanket, was derailed. The train could not be re-railed while the snow lay so deep, and thus was forced to sit at the Tenino station. Despite the winter white, the temperature was not particularly cold, nor did the wind blow very strongly, and the passengers remained fairly comfortable during the wait. A locomotive with a snow plough finally arrived, and snow was cleared enough to put the ditched train back on the track. This did not end the problems. Landslides buried many sections of track to the south, and temporary paths had to be laid over these blockages. Fortunately, very few trees were toppled along this stretch of railroad, or the trip would have taken even longer. With the train's final arrival at Kalama, information was then transferred to the Astoria boat, which then had to sail to Portland. Storm reports from regions that in today's era of modern highways and automobiles seem very neighborly were, in fact, delayed by days, and in some cases weeks, because of the communication line disruption. This included damage to roads, bridges and rails. Some reports from the Willamette Valley didn't reach the Oregonian until January 13th. Messages from Seattle were delayed longer: "There has been no communication with the Sound country since last Friday morning," it was written in the same January 13th issue. The deep snow up north prevented the wires' immediate repair. Even on the 16th, a week later, the Seattle-Portland connection was still reported broken. Coastal communities, which had the added problem of getting dispatches across the densely forested Coast Range, took even more time to report. Information from Newport, for example, wasn't printed until the 17th, and Coos Bay's story wasn't printed until January 19th. In the modern era, even if the telecommunications grid was down and power shut off over large regions, radio powered by generator, satellite, and even aircraft would bring in information at a much quicker pace. The list of damaged and destroyed barns, toppled sheds, wind-thrown houses (some were wind-rolled), injured and killed livestock, smashed bridges, prostrated fences, and tree-blockaded roads throughout the northern Willamette Valley and on the central Oregon coast is huge, and would fill many pages. Though the hard data isn't available for direct comparison, it seems evident that the January 9, 1880 windstorm was a window onto the destruction that would visit the entire valley, and indeed most of the Pacific Northwest, in 1962. What follows are some specific accounts of structural damage. At Newport, the "front of the town was washed and damaged considerably, as the tide was high and the bay as rough as the ocean itself" [16]. At least eight barns collapsed in the vicinity, one of which caused the deaths of two cows. A residence was destroyed, and "temporary buildings, sheds and fences were laid low." In Benton County, a blacksmith shop was destroyed, and many small buildings flattened. The house of a doctor was "thrown down;" the family, which included six children, escaped just ahead of the collapse. A church steeple also toppled. Many signs were prostrated, loose lumber tossed about, and some chimneys were shoved over by the four-hour gale. In Linn County, a large stock shed that housed "seven fine horses" was crushed by the wind; all the horses were injured, but not seriously. Harmony Grange Hall was destroyed, a 100-foot-long hay shed was badly damaged, and a barn lost half its roof. A church at Harrisburg was shoved off its foundation and its top was out of plumb in a northward direction by two feet. In Albany, a "great many chimneys were upset." In Polk County, at Buena Vista, "Four barns, a number of woodsheds, smokehouses and various other buildings were blown over." The roof of a pottery building also sailed off. The January 10th and 12th, 1880 Oregonians reported these losses for the area immediately around Portland: destroyed houses: 12, damaged houses: 6, destroyed businesses: 3, damaged businesses: 11, destroyed hotels: 1, damaged hotels: 4, destroyed churches: 2 (one doubled as a school), damaged churches: 1, damaged schools/academies: 2, destroyed sheds: 5, damaged sheds: 1, destroyed barns: 1, damaged barns: 1, damaged halls: 1, damaged livery stables: 1, damaged conservatories: 1, damaged courthouses: 1, damaged docks: 1, damaged railroad buildings: 2, destroyed windmills: 1. Dollar losses were reported for about half of these wrecked structures, and totaled $19,825. That figure, adjusted in relation to the United States GNP in 2000, reflects the loss of about $1 million [17]. Portland's total damage estimate climbed to about $100,000 ($5 million adjusted) with the count of damaged structures exceeding 100, and estimates of $1 million in damage throughout Oregon were reported ($50 million adjusted) [18]. These figures do not account for the dramatic increase of population, and related property, from 1880 to 2000, which would produce much higher results. The population of Portland in 1880 was mere 17,577 [19], and by 2000 it had reached 529,121 [20]. Assuming a linear increase in total property that is directly related to the population figures, then the damage estimates increase about 30 times, which puts the storm close to the damage wrought by the Columbus Day Storm [Footnote 4]. Elsewhere in Multnomah County, the Mt. Tabor church was torn from its foundation and rolled down the hill intact [21]. St. Francis Catholic Church, in East Portland, was smashed. A bridge near "J. W. Kern's place" was crushed by falling trees. Several wagons were destroyed in a collapsed paint shop. A delivery wagon was yanked from an elevated road near Wiedler's Mill, and had two wheels smashed. On First and Front Streets, nearly every tin roof was disrupted. So many roofs were damaged throughout Portland that, in a single day, tin prices rose from $7.59 to $10.00 per square. Roofs weren't the only things made of tin: a bulky ventilator on the post office was yanked from the roof and dropped into the yard of the Central schoolhouse. Slate shingles also leaped from the postal building, and some struck pedestrians downwind, though no serious injury resulted. No less than 27 head of livestock were killed in the area between Portland and Revenew. The Vancouver Barracks lost several buildings valued at $2,000 to $2,500 dollars. In the St. Helens area along the Lower Columbia, which generally escaped major damage, one house toppled. People in the community gathered together and quickly constructed a new home on the spot where the old one had stood. Schools were ravaged throughout the region. The schoolhouse in the Blodgett Valley, Benton County, collapsed [22]. In Linn County, at King's Prairie along the north fork of the Santiam River, the learning center was demolished by collapsing timber. The school in Lebanon was shaken up badly. At Salem, the Willamette University building was damaged, but classes had resumed on the 12th even despite the frayed structure. The Sisters' school was also badly damaged-rough boards had been hastily put on the roof to prevent further damage from heavy rains that followed the storm on the 12th. In Portland, at noon on South First Street, St. Matthew's Episcopal Chapel, which was used as a schoolhouse for 60 pupils during the week, collapsed. As the wind grew fearful from 11 to 12 o'clock, which alarmed the residents, class had been dismissed just moments before. St. Mary's Academy, also in Portland, lost the top of its spire. At the North School, two chimneys toppled and crushed a couple of interior partitions, prompting the early dismissal of students. Yamhill County's new public schoolhouse, built at the cost of $4,000 in McMinnville, was suddenly shoved sideways by the gale, with much cracking and popping. Class, in session at the time, was immediately dismissed for fear that the entire structure would collapse. At least three fatalities resulted from the high winds, two in La Center, and in a school house [23]. At 12 noon, the recently constructed schoolhouse was struck by the only tree left close enough to hit the building. The 24 pupils and their teacher were having lunch around the central stove, when the wind-thrown bole crashed through the roof. Olive, age 9, was killed instantly, and Alex, age 7, died shortly after from mortal wounds. Three children suffered severe injury. Only one child escaped without being hurt, and some were burned from a fire that started from the smashed stove. Many people were trapped under the rubble, and could not escape the growing flames. Quick work from a bystander, and some of the older boys who managed to free themselves, doused the flames before they added to the tragedy. In downtown Portland, fifteen people raced for the door as Bremen Hall cracked under the strain of the lashing gale, and plaster fell from the ceiling [24]. Four were caught in the two-story building's total collapse. The bartender, Harry P. Heinrich, was killed, and the cook, Walter Vivian, was badly injured. Jack O'Donnell, a former track layer, was so badly wounded that he was initially reported dead. Joseph Hillshaw, a longshoreman, suffered light injury. The two severely hurt were taken to St. Vincent's, and were reported in good care. Two fatalities are attributed to the snowstorm in Washington [25]. Saturday evening, a young clerk for the Puyallup train station grabbed his blankets, then headed home. He was found Sunday morning, frozen to death just a few yards from his house. Another man was found near the Yelm train station, a few steps from the track, also frozen. Storm-related injuries were scattered across Oregon. In Portland, a man walking over a bridge was struck in the face by a plank that had been torn loose; he fell over the side and suffered a fractured leg [26]. A man on Flander's Dock, in Portland, was blown into the river, and quickly rescued. While walking home from work, another man dropped through a shattered sidewalk, and gashed his chin. There were many comments throughout the articles in the Oregonian about the few, and in most regions no, fatalities and scattered injury caused by the storm. Considering the high loss of trees, it does seem rather lucky that so few people were killed or hurt. The low population densities at the time probably had a hand in this, but even the largest storms later in history, like Columbus Day 1962, haven't produced casualties even close to the scale of some eastern hurricanes. Forty-six deaths resulted from the Columbus Day Storm in California, Oregon and Washington combined, whereas the Galveston, Texas, hurricane of September 1900 took the lives of 6,000 people, the September 1938 "Long Island Express" stole about 600 lives in New England, and 256 died from hurricane Camille, August 1969 [27]. Maybe there's a certain luck that goes with being a northwesterner! The more likely explanation is the fact that the Pacific Coast is comprised of steep terrain, and most of the population lives above the reach of storm surge flooding, which has been the largest contributor to deaths in hurricanes. Finally, amid all the grim destruction reported above, it seems that this narrative should be ended on a lighter note. During the era of this storm, Oregonian reporters always seemed to be on the lookout for the humorous side to a situation, and on January 10th, it was reported: "The night watchman and the O. S. N. Co.'s office is a boss sleeper, having slept through the entire din and clatter of the storm. He was oblivious to everything and knows less concerning the storm than any man in the town." January 9, 1880: Storm Data A fair amount of the available storm climatology was disseminated above. As mentioned in the beginning of this section, wind records are limited from the 1880s era, making it difficult to pin specific figures over a broad region. Portland, officially, had a peak wind of 50 mph, and other stations ranged from 65-80 [28]. These appear to be average speeds--the Signal Service appears to have reported wind data in 15-minute averages. Instantaneous gusts were significantly higher. As reported in the Oregonian, January 10th, 1880, steady gusts of several minutes duration climbed to 60 mph at Portland, and short bursts "of few seconds duration" reached at least 70 mph. Seventy mile-per-hour gusts will produce a fair number of windfalls, but, as demonstrated at Eugene in 2002, the majority of timber tends to survive the onslaught. In the worst situations, where trees have been weakened by other factors, such as drought (which kills roots) or saturated ground (which reduces root-soil cohesion), a blowdown rate of a few percent might be expected from this kind of wind. According to the Windthrow Handbook, few trees can survive winds that average 60-65 mph for 10 minutes or more [29]. Since Portland's reading of 50 mph at 2 PM was probably a 15-minute average, and occasional gusts upwards of 60 mph sustained for several minutes, it seems that the winds were close to the minimum value for wholesale tree destruction right in the city. In the south Willamette Valley, during the Columbus Day Storm of 1962, sustained 1-minute wind speeds of 58-63 mph yielded peak instantaneous gusts of 86-90 [30]. The Columbus Day Storm appears to have been a bit gustier than a typical windstorm. Even so, a wind with an average of 60 mph for 10 minutes would probably throw short gusts even higher than the readings seen in the storm of '62. From this knowledge, instantaneous wind gusts for the January 1880 windstorm can be estimated in the 85-90 mph range, possibly 95-100 mph, for select regions between Salem and Portland that had reports of near total blowdown, including most of Clackamas County, eastern Washington County, and north of Portland in parts of Clarke County, Washington Territory. From the damage described to trees and structures elsewhere, winds probably reached 60 to 75 mph at times between the greater Corvallis area and Salem, with higher gusts in the Cascade foothills, and along the west side of the Willamette Valley up to the Sheridan-McMinnville-Newberg line. In the Lower Columbia River region, short-duration gusts probably reached 50 to 65 mph in the northwesterly blast that arrived with the bent-back occlusion. It should be noted, however, that the Signal Service employed the use of 4-cup anemometers, which read high when compared to the modern 3-cup anemometers. An indication of 50 mph was actually more like 40 mph when adjusted to the newer wind equipment. This adjustment would also affect the 60 to 70 mph short-duration winds measured, which reduces the storm at the Signal Service office to about 40 mph gusting to 60, which is a reading typical of many windstorms. I also did a survey of treefalls across a railroad track near Veneta, OR, after the February 7, 2002 windstorm (detailed on the February 7, 2002 webpage). The count yielded 62 trees across 0.75 mile of track for certain, which generates a figure of one tree down per 61 feet, which is comparible to the average of the many figures quoted far above in this document. Many of the toppled trees were in swaths like those described in the same anecdotes, producing areas with a very high density of windfalls and others with hardly any sign that high winds had occurred. Sustained winds at the nearby Eugene Mahlon Sweet Field reached 49 mph gusting to 70 in the 2002 storm. Thus, from this limited excercise, it seems that 50 mph gusting to about 70-75 mph is probably a good figure for peak winds at many areas during the January 9, 1880 Great Gale. Saturation of ground and snow loading can play a big part in generating windthrow. In the January 9, 1880 Oregonian, the Signal Service reported that 7.16" of rain had fallen on Portland in the week ending January 7th. This is a heavy total. And rain had continued, with 0.35" falling in 24-hours by 8 PM on the 8th. The Willamette River had risen one foot and two inches by 1 PM on the 8th (probably a 24-hr change). In the January 16, 1880 Oregonian, the Signal Service report for the week ending January 14th noted an additional 2.71" of rain. It is clear that the ground was saturated during the windstorm, and this almost certainly contributed to the windfalls. The effects of snowloading were already described at Fort Clatsop, and this probably played a role in some of the windfalls mentioned at Kalama. These secondary factors also support the idea of not-so-extraordinary winds in the Willamette Valley, which is also why I suggest 50 mph gusting to 75 as a good bet at most locations severely affected by the 1880 storm. For the most severely flattened areas, such as just south and east of Portland's downtown and in Clarke County, it is possible that brief wind gusts reached 80 to 90 mph. Incidentally, Portland's lowest temperature for the week ending January 14th, 30° F, happened on the morning after the storm, another mark of the cold air wrapped around the low's trailing side. The Storm King: A Brief Climatology Have any storms in more recent times followed a similar track to the one described for the 1880 cyclone? The answer is yes, though the storms haven't been as deep, nor have they been as cold, with one being outright warm. About five months after the Columbus Day Storm, on March 27, 1963, a low tracked inland on nearly the same path as shown in Figure 4 [31]. This storm had flip-flop winds, however, with the strongest gusts being 75 mph recorded at Eugene, and decreasing to about 62 mph at Portland. About four-and-a-half years later, on October 2, 1967, there's a much stronger example. A fairly deep low nearly passed over Portland, and kicked up a terrific wind in the Willamette Valley. Sustained velocities of 70 mph with gusts to 78 hit Portland, and bursts reached as high as 58 at Eugene. This second storm more closely fits the 1880 wind pattern, but has a complete lack of lowland snow. Temperatures remained in the mid 50s in western Washington during this event, due, in part, to the early season nature of the storm--there simply wasn't any particularly cold air anywhere in the region. The October 1967 and March 1963 will be examined in future pages on this website, with both cyclones being compared to the January 1880 Storm King. Media Note This web page was featured in a Sunday, January 11, 2004, Olympian article by John Dodge, in his Soundings column, article title "Recent weather pales mext to 'Storm King'." Many thanks for the attention! Footnotes 1. It is important to recognize that "blowdown" has different meanings depending on where it is employed. Researchers of forest ecology, who study the effects of windfalls on forest health, consider a blowdown to simply be an area where near total loss of trees has occurred (also known as a swathing and windthrow). Often, these forest disturbances happen in small pockets. In a study by Nowacki, Gregory J., and Kramer, Marc G., in "The Effects of Wind Disturbance on Temperate Rain Forest Structure and Dynamics of Southeast Alaska," USDA PNW General Technical Report 421, April 1998, such blowdowns typically ranged from 1 to 1,000 acres. 2. The Columbus Day Storm produced a 0.26" rise in one hour at North Bend. An extreme rise in its own right, it was the largest jump in the Pacific Northwest measured on that date. Out of all the windstorms examined in this study, the fastest one-hour rises were 0.41" at Hoquiam during the November 3, 1958 windstorm--the low's center almost passed right over the station--and 0.42" at North Bend during the February 7, 2002 event. 3. This is probably due to the fact that people were "closer to the land" in the 1880s, as the region's economy was strongly dependent on forest and agricultural products. Over about a century, this changed, as an increasing number of industrial and high technology firms moved into the Willamette Valley. Along with the new businesses arrived a growing population with less attachment to the land (in terms of their financial livelihoods being directly related to it), which seems to have helped push reporting away from a natural history agrarian-type orientation to a more home-owner-in-the-suburbs property-minded one. 4. The Columbus Day Storm caused $170 million in damage to Oregon in 1962 dollars. Adjusted for inflation out to 2000, this jumps to about $850 million. The increase in population (and related property) between 1962 and 2000 doubles the figure to about $1.7 billion, which is easily within an order of magnitude of the $1.5 billion estimated for the Storm King of 1880. References [1] Kruckeburg, Arthur R. "The Natural History of Puget Sound Country." University of Washington Press. 1991. Pages 51-52. [2] Timber losses for the Columbus Day Storm are from (1) Lucia, E., The Big Blow, p 64. (2) Windstorms, a safety brochure produced by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2002 (this document contains the higher figure of 15 billion board feet). [3] Timber losses for the January 29, 1921 and December 4, 1951 windstorms are from Decker, Fred W., Cramer, Owen P., Harper, Byron P, "The Columbus Day 'Big Blow' in Oregon," Weatherwise, December 1962, page 244. [4] Mt. St. Helens blew down at least 1 billion board feet, according to Foxworthy, Bruce L., and Hill Mary, "Volcanic Eruptions of 1980 at Mount St. Helens, The First 100 Days," Geological Survey Professional Paper 1249, United States Government Printing Office, 1982. [5] The Daily Oregonian, January 19, 1880. Other reports of light damage: Hillsboro, Forest Grove, and Eugene, January 15, 1880, Mouth of the Columbia, January 12, 1880. Severe gale or damage: Newport, January 17, 1880. Southwest Oregon, including Coos Bay, Gardiner, Oakland, Roseburg, January 19, 1880. Salem, including snow, January 13, 1880. [6] Some of the information for Salem, including the time the snow began, is from a clipping file for the "Great Gale of 1880" at the Oregon Historical Society, in article titled "Wind Rages" (90). [7] Reports from Olympia, Seattle, and Vancouver in the Oregonian on January 19, 1880. Deep snow in Seattle and Port Townsend (with damage reports), and reports from Fort Clatsop, January 13, 1880. Kalama reports on January 12, 1880, and then again on January 14, 1880 (with snow depth for Tacoma), "The Recent Storm," On the N. P. R. R. section. First storm (January 7th and 8th) in Astoria, on January 9, 1880. [8] Oregonian, January 19, 1880, "Storm Hits Clackamas and Yamhill Counties," for the Clackamas and Yamhill County areas. Salem, January 13, 1880, "Additional Storm News," Salem section. Multnomah County January 10, 1880, "The Storm King". Hubbard, January 12, 1880, Northern Marion Co. section. Benton and Polk Counties January 17, 1880. [9] Oregonian, January 10, 1880, "The Railroads," railroad problems for Portland. Also January 12, 1880, "Along the O. & C. R. R." for conditions of track down the Willamette Valley. And January 13, 1880, "Additional Storm News" West Side section. [10] Oregonian, January 10, 1880, "The Shipping," shipping problems for Portland. Astoria, January 12, 1880. [11] Story of the Dixie Thomson was reported in the Oregonian on January 12, 1880. [12] Story of the Idaho was reported in the Oregonian on January 13, 1880, "Additional Storm News," Upper Columbia section. [13] Telephone patent information from Bunch, Bryan, and Hellemans, Alexander. "Timetables of Technology." Touchstone Press. 1993. Page 274. [14] Oregonian, January 10, 1880, "Scenes and Incidents," for communication details in the Portland area. January 12th, 1880, "Along the O. & C. R. R." for additional details. [15] Oregonian, January 14, 1880, "The Recent Storm," Along The N. P. R. R. section. [16] Oregonian, January 17, 1880 for Benton County, Linn County and Polk County. St. Helens area, livestock deaths, Vancouver Barracks, January 13, 1880, "Additional Storm News," From Various Sections section. [17] Brooks, H. E., and Doswell, C. A. III. Normalized damage from major tornadoes in the United States: 1890-1999. May 12, 2000 and September 7, 2000. Weather and Forecasting, Vol 16, p 168. The method of using GNP and Consumer Price Index presented in this paper are employed here, and in other parts of this website. [18] From the Oregon Historical Society Scrapbook 55, page 66, in an article titled, "Gale of 1880 was Real Blow." [19] 1880 population for Portland is from a clipping file on the "Great Gale of 1880" at the Oregon Historical Society, in an article titled "Recent Northwest Storm Recalls Violent Weather Disturbances of Oregon" (5064). [20] 2000 population for Portland is from "Certified Estimates for Oregon, Its Counties and Cities, July 1, 2001," from the Portland State University Population Research Center. [21] Damage in Multnomah County from the Oregonian, January 10 and 12, 1880, "The Storm King", and "Friday's Tempest". [22] Oregonian, January 17, 1880, "Benton County." Other school damage reports in this paragraph were Linn County, January 17, 1880, Yamhill County, January 19, 1880, Portland, January 10, 1880, and Salem January 13, 1880. [23] Oregonian, January 16, 1880, "The La Center Horror." [24] Oregonian, January 10, 1880, "The Storm King," and January 12, 1880, "Friday's Tempest" City section. [25] Oregonian, January 14, 1880, "The Recent Storm," On the N. P. R. R. section. [26] Oregonian, January 10, 1880, "East Portland," injuries for Portland. January 12, 1880, "Friday's Tempest" City section. [27] Fatalities from hurricanes are from Simpson, Robert H., and Riehl, Herbert. "The Hurricane and its Impact." Louisiana State University Press. 1981. Page 21. [28] Taylor, George. 1997? "Oregon Weather Book." [29] "Windthrow Handbook for British Columbia Forests." Ministry of Forests Research Program Working Paper 9401. 1994. Page 14. [30] National Climatic Data Center, Unedited Surface Observation Forms for Eugene and Salem. October 12, 1962. [31] National Climatic Data Center, Unedited Surface Observation Forms for Portland and Eugene. March 27, 1963, and October 2, 1967. |

Page Last Modified: January 13, 2004 | Back | |